Stay Focus, Look Professional: A Breakdown of the NHL Dress Code

I thinks it's time we have a long overdue chat on the relevency/need of a dress code in the National Hockey League.

On March 4 & 6, 2023, I shared a series of TikToks on my personal page (@offcarlagoes which you should follow) where I shared some of my grievances with the NHL dress code. Due to the concise nature that is required of a TikTok for it to do well, I didn’t get to share my fully formed thoughts on the subject. Consider this to be my full fledge, honest and possibly drawn-out and overintellectualized opinions on the matter.

And before anyone asks what my credentials are to speak on such high authority on the NHL dress code, well, I spent the past 19-ish consecutive weeks watching what almost. every. single. NHL. player wears to gameday. And every single week, I would compile the best/my favourite ones and share them on Tiktok. While I'm not quite as knowledgeable as Sara Civian, who originated the NHL Style Power Rankings on The Athletic and BR Open Ice (with whom NHL Fave Looks of the Week would not exist), I like to believe I'm one of the more informed people in the NHL fashion business.

[P.S. English is not my first, nor second language so there might be a few grammatical/syntax errors here and there, so please be kind and keep that in mind.]

Exhibit 14 of the NHL’s Collective Bargaining Agreement outlines various rules of conduct for NHL players, ranging from “[p]layers must be on time for all Club practices, games, meetings and other mandatory Club events,” “[g]ambling on any NHL Game is prohibited” to “[f]ans are to be treated with respect and courtesy. Autograph requests in the vicinity of Club facilities should not be unreasonably denied”. In the midst of those rules is the infamous Paragraph 5. The rule goes as follows:

“Players are required to wear jackets, ties and dress pants to all Club games and while traveling to and from such games unless otherwise specified by the Head Coach or General Manager”.

Some teams, such as Lou Lamoriello’s Islanders, have stricter dress codes than what is required by the NHL. Lamoriello, an old-school GM, bans facial hair, long hair, and excessive jewelry. He enforces his dress code under the belief that “individual players can help you win games, but teams win championships.” Thus, everyone looking the same and sacrificing their individuality in the name of being a unified team, both in appearance and mindset, contributes to a winning environment and a strong team culture.

On the absolute opposite end of the spectrum, you have the Arizona Coyotes. Oh boy. The Coyotes receive a lot of warranted criticism for being an absolute mess of an organization. But one aspect in which they really thrive is their dress code or lack thereof. Shortly before the start of the 2021-2022 NHL season, Coyotes chief brand officer Alex Meruelo Jr. in consultation with former team captain Oliver Ekman-Larsson decided to lax the dress code after the previous year’s bubble season. Thus, Coyotes players are allowed to show up in basically anything. And they take full opportunity of it, it’s not uncommon to see them show up in jeans, graphic tees, casual dress shirts, bomber jackets, etc.

"To be the first team to go no dress code was awesome. The guys loved it. I think it's great to be able to show a bit of your personality and your closet other than just your suits. I had fun with it. I enjoyed it. I'm glad it's something we'll continue to do." - Jakob Chychrun to ESPN (2021)

Somewhere in the middle, we have the Toronto Maple Leafs. Under Lamoriello, the Leafs maintained a strict clean-shaven suit and tie combo, but under Kyle Dubas’ reign as GM, they have attempted to strike a balance. Players are still technically required to wear a suit, but they have some amount of flexibility (i.e., they can wear a coat instead of a jacket, not wear a tie, sneakers instead of dress shoes, etc. ). Some wear non-traditional colours such as William Nylander in pink or Morgan Reilly in burgundy red. As a non-fan of the Leafs, I’ve come to know Michael Bunting for his impressive collection of eccentric socks. It’s not uncommon to see Auston Matthews, who has a reputation around and out of the league as being stylish, wearing designer brands such as Louis Vuitton, Dior, Kith or Gucci. Mitch Marner’s outfits are often accompanied by an assortment of godforsaken hats.

This article is not meant to be an academic essay by any metric. And while my goal in writing this is, in a way, to try to convince you that the NHL should drop the dress code, at the end of the day, I’m just trying to show you that no matter how banal you may think caring about what a player wears in the five-minute walk from his car to the dressing room and back, it actually is a nuanced subject. While I firmly sit on the Abolish the dress code side of the argument, I do kind of get where the people who want to maintain the dress code come from.

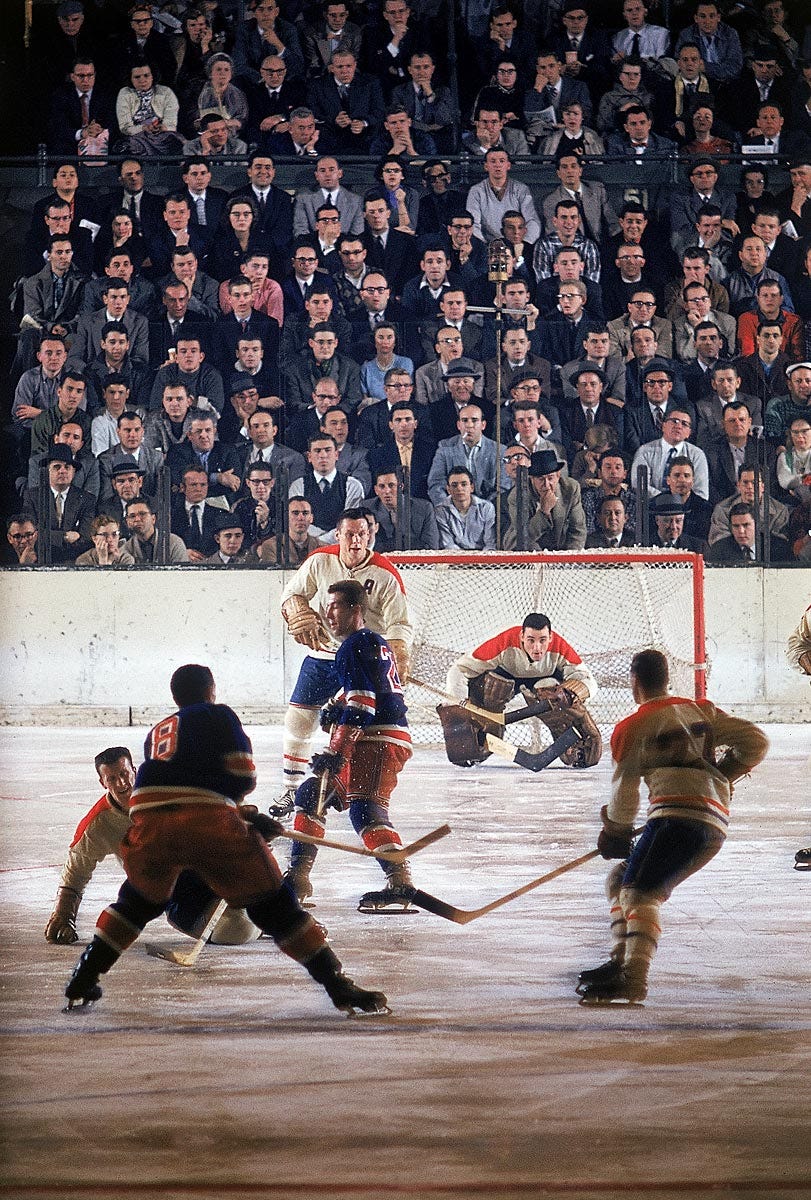

A Brief-ish History of Hockey Players in Suit

The dress code is probably not as old as you think, more precisely it came about in the 1995 CBA. Of course, players were wearing suits to game days long before that. Why? While I don’t have the exact reason why, I can only surmise a few reasons that make historical sense, at least to me. In 1921-1922, Newsy Lalonde regarded now as “one of hockey's and lacrosse's greatest players of the first half of the 20th century and one of Canadian sports’ most colourful characters,” only made about $2000 ($29,917, adjusted for inflation) for the entire NHL season. And he was the highest-paid player in the league at the time. Back in the 1920s, the term “professional” sportsmen had a very different meaning. Early teams in professional sports were run on shoestring budgets, with players being paid as little as $100 to $300 a game in a truncated season, and they were often traded for similar sums. I believe that the suit, back then at least, served as a sort of equalizer of the class divide. You can’t really tell who is rich and who is poor if everyone on the team is wearing a suit. In that way, it does manage to create the team culture of everyone pulling their weight no matter where they come from which Lamoriello boasts about.

Furthermore, suits are nowadays considered to be formal/professional attire. The suit first worn in the 17th century by King Charles II was codified in the 1800s as being the uniform of business and the aristocracy. By the mid-twentieth century, suits had trickled down to the working class as well. The wearing of suits had become a social norm, and the large-scale mass production of suits in post-WWII had made them more affordable to the average man. Thus, prior to the Casual Revolution of the 1960s, wearing a suit, especially, if you were upper/middle class or higher was just considered normal. In a time before merchandising became commonplace, people used to go to hockey games dressed to the nines in full suit-tie-and-hat. So, it goes without saying that a player showing up to a game in a suit was not anything out of the ordinary as the suit was just what every man wore.

Why Have A Dress Code?

Possible Theory #1: Enforced Conformity

The worst offence an NHL player can find himself guilty of, beyond that of shooting a puck in your own net or committing a literal felony, is that making himself bigger than the team. The best example of this lies with one PK Subban, which I was lucky enough to experience first-hand. If you weren’t around Montreal during the PK years, it might be hard to grasp how much the man was beloved by the city and by extension the province. And for a province that’s maybe not known for its openness to people who don’t embody the image of a “Québécois pure-laine”, the fact that a Black Ontarian Anglophone man was able to be so widely loved by almost every and anyone, is nothing short of spectacular. In theory, it was a match made in heaven as Montréal and Québec loved PK and PK loved them back equally, so nothing could ever go wrong, right? Right?

Subban drew attention to himself by wearing flashy clothes and pledging to donate 10 million dollars to the Montreal Children’s Hospital off-ice. While PK’s loud and exuberant personality is what made him win the affection of fans, to an old-school Canadiens executive group and certain teammates it made him intolerable. Subban serves as an incredible case study of how conformity is integral to the NHL philosophy and how the dress code fits into that. In hockey, poor dress gets too often confused with poor behaviour. Players like PK, Evander Kane1, or Ray Emery get flack for dressing too flamboyantly, for not being humble enough, or for not conforming to the unwritten NHL standard of conduct. In 2016, the Montreal Canadiens, unexpectedly, traded Subban for Shea Webber, the then-captain of the Nashville Predators. Not to diminish the on-ice talent of Weber, but the fact that he is the literal embodiment of a gritty and humble Canadian most definitely had a role to play in the trade.

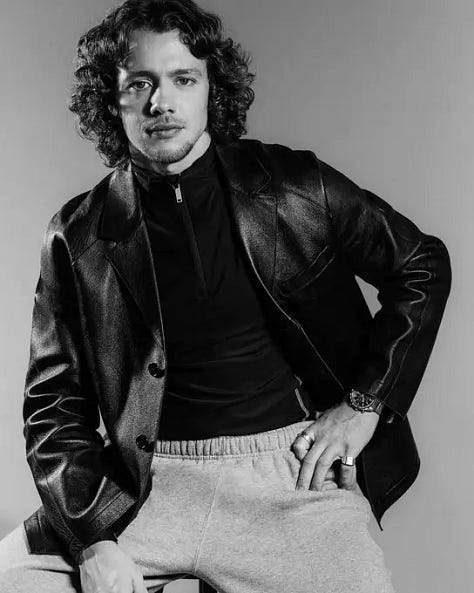

And this expectation of conformity is not unique to just Black and other POC hockey players. European players also face some amount of scrutiny for having to conform to the North American standard of a hockey player. In an interview with Sports Illustrated, Henrik Lundqvist, who is undoubtedly one of the most stylish men to ever play the game of hockey, revealed that his fashion sense also stood out

I think it fit in with New York but it didn’t really fit in with hockey. I remember all of the older guys, they were making fun of my suits, my skinny ties and my skinny jeans. But for New York, it blended it right away. But now you see a change a little bit in hockey with the younger guys, they care a little more about fashion. But it’s funny, if I compare myself to regular Swedes or people here in New York, I don’t see myself as very fashionable. - Henrik Lundqvist

However, that amount of scrutiny is nothing compared to what players of colour face for going “off-code”. In contrast, a player like David Pastrnák or Patrik Laine gets revered for the often campy and over-the-top outfits they show up wearing on game days, but that grace only gets extended to some.

Possible Theory #2: The Suit Serves as a De-Facto Marker of Masculinity

There’s a tendency amongst older folks, although this sentiment is not exclusive to an older demographic, that hockey has become too soft. Following the decline of bodychecking and fights that have occurred in the NHL in the past few years, there’s a margin of people who lament the absence of grit and toughness that was present in the “good old days of hockey”. Don Cherry is the emblematic spokesperson of the “hockey has gotten too soft” narrative. In an article on Canadian state celebrities, Cherry is described as “pro-hockey fighting, pro-aggressive masculinity, pro-military, and jingoistic. He was one of the early NHL opinion leaders decrying the influx of European players into the league – ‘chicken Swedes’ as he called them. He is famous for his condemnation of ‘do-gooders’, ‘pukes’, and ‘pinkos.’”

This condemnation of ‘softness’ and wanting to reinforce the NHL player as a gritty, masculine man plays into my second theory on the dress code. The suit is probably the most masculine thing a man can wear. Tim Edwards, a prolific scholar on the topic of masculinity, defines the suit as being “in a sense, the very essence of men’s fashion and, indeed, masculinity”. The suit represents not only masculinity but hegemonic masculinity. Famed sociologist, R.W. Connell defined hegemonic masculinity as the benchmark against which all other forms of masculinity are judged. The societal expectation of men is that they do not care about the clothes that they wear. Caring about fashion is perceived and has been historically relegated as something that is typically feminine. In the grand scheme of everything you could be wearing, a plain navy or black suit is boring: devoid of any uniqueness or distinguishing element. The wearer of a suit becomes anonymous and ubiquitous: the image of impersonal authority. The suit is often understood as emblematic of dominant masculine ideals. In Psychology of Clothes, author John Flügel remarks that the suit represented a shift in men’s clothing away from flamboyancy and individuality to modesty and uniformity, a “great masculine renunciation” of fashion in favour of universal brotherhood at the end of the eighteenth century. Furthermore, a study conducted by Barry and Weiner that interviewed men on their dressing habits found that for men wearing a suit was a disguise that shielded them from being found out as frauds in their masculinity.

To return to the “hockey has gotten soft” point, the NHL is the only North American professional sports league that still has a dress code. The NHL’s core viewer demographic is whiter, older and more conservative than that of the other big three North American Leagues (NFL, MLB, NBA). At least on the Internet, many of the fans who tend to be the most vocal and resistant to changes in the league tend to fall into that demographic. I imagine that for those people, opening up the dress code to include more than a suit is perceived as a threat to the “manliness” of hockey. Especially when you take into account the fact that a lot of hockey fans compare the NHL to the NBA. In turn, they like to mock NBA players as being “softer, flashier, self-centred” in comparison to the “gritty, manly, humble” NHL players and to me, those beliefs extend to their sports respective dress codes.

Addendum #1: Don Cherry’s stance as an advocate of masculine, working-class hockey is an evident contradiction to the bright, flamboyant suits he used to wear on Hockey Night In Canada. There is an academic article on Imaginations that dives deep into the symbolism of Don Cherry’s suits that I highly recommend reading.

Addendum #2: A critique that I often get in my Tiktok comment section when I do FLOTW is that NHL players don’t have time to choose their outfits. Believe it or not, most of your favourite NHL players not only have personal/team stylists but also get their suits custom-made during the off-season.

Possible Theory #3: The “Professionalism“ Argument

The professionalism argument is that wearing a suit is a marker of professionalism.

Don Cherry while commenting on Sidney Crosby once said, “Look at him kids, dress like him. Don’t dress all slovenly. You see basketball players walking in they look like thugs, same thing as baseball and the whole bunch. We got class!”

Another article written on this subject, Clothes Maketh the Man: The NHL Dress Code and Conformity articulates this far better than I ever could. “The emphasis on a professional and clean image is really to appeal to white corporate anxieties about the ‘hip-hop’ image of basketball (Leonard, 2012). Black bodies were perceived as violent and dangerous, especially after a black player fought with a fan on court (McDonald & Toglia, 2010). Conversely, white bodies and corporate aesthetics of professionalism are considered normal and civil (McDonald & Toglia, 2010). Professionalism can “functions as a stand-in for whiteness, signifying goodness, respectability, and desirability” (Leonard, 2012, p. 165).

While Don Cherry is not necessarily where this conversation around professionalism starts, he has certainly made himself abundantly clear about how hockey players should dress and that conservative rhetoric has carried through the years under the guise of respect and tradition.

I’m going to be transparent here, the professionalism argument is one that has never made sense to me no matter how many times people try to explain it. I get the whole you’re here to represent the city/state of the team that you’re playing for, so you better look the part. But these are mostly men in their 20s/30s chasing after pucks, or hitting other grown men against the boards for millions of dollars. They are not defending a case in front of the Supreme Court or performing open heart surgery. And if they’re meant to represent the city/state, why not just have them wear team paraphernalia? Never in my entire life have I heard that Tom Brady is inherently unprofessional because he showed up to work in a bomber jacket or a sweater. I understand that there needs to be rules of decorum because in most workplaces you can’t show up in pyjamas and slippers. But why is Dwayne Wade in a Ralph Lauren sweater and a white trench coat seen as less professional than Nikita Zadorov in a brown plaid suit?

Addendum #3: Overconsumption/Sustainability: There is a valid argument to be made in the favour of the dress code that I don’t think I’ve ever seen being made online or in any other place. Of the 100 billion garments produced each year, 92 million tonnes end up in landfills. If your dress code requires you to wear a suit for 82 games a season, it’s easy to only buy a handful of suits and just rotate between them throughout the year. The suit is the adult male version of a uniform, and most normal people (not me) don’t spend their time guessing if a player is re-wearing the same suit from three games ago. One then could argue that a suit dress code is a lot more sustainable than having to plan out 82 different outfits with a stylist.*

*At least in the context of red carpets, clothes are loaned from a designer to a client and returned back after the event is over. I don’t know if stylists also use the loaning system for everyday wear.

Addendum #4: Just to be clear, I’m not implying that liking the dress code makes you a racist/misogynist/proponent of violence whatsoever. I’m just highlighting some of the problematic rhetoric that surrounds the dress code/general hockey culture.

Reasons for Change

Marketability

It is a truth universally knowledge that the NHL is notoriously bad at marketing the sport of hockey outside of its core demographic.

An example of the NHL’s mismanagement of their brand outreach through fashion however can be found in the King himself, Henrik Lundqvist. While I have no concrete data to prove my following assertion, everyone loves Henrik Lundqvist. He’s Swedish, plays guitar, is charismatic, well-spoken and has his own charity that focuses on providing education and health services to children. Marketing-wise, the man is a slam dunk for any marketing executive that is lucky enough to get their hands on him. Lundqvist was also well known for his impeccable fashion taste. Over his fifteen seasons in the NHL, he topped several major publications’ lists for best-dressed hockey players, athletes or notable personalities. In my view, the NHL messed up badly by not trying to lean into his appreciation for fashion to generate a more cross-cultural audience for him.

Lundqvist was drafted by the New York Rangers and lived in New York City for fifteen years. He frequently attended both Milan and New York Fashion Week. If I was in charge of marketing at the NHL, I would have filmed the whole thing for content. No one ever taught of calling up Ralph Lauren, or Tommy Hilfiger to try and make him a brand ambassador. No one ever had the idea of trying to get him to collaborate with a fashion house to make a collaboration collection. In both the 2017-2018 and 2018-2019 seasons the New York Rangers did not make the playoff, so no one taught about trying to get him a last-minute Met Gala invite*?

In contrast, the NBA was quicker to recognize how fashion could bring in big bucks and more publicity for its players. In 2008, LeBron James was photographed wearing Beats by Dre headphones to a US Olympic Men’s Team game. The headphones sold out almost immediately and the company gained immense popularity. Since then, the NBA’s concrete runway, the tunnel between the garage and the dressing room serves as a platform for players to market their partnerships or collaborations with the designers. The Instagram page leaguefits, which has more than 889,000 followers, chronicles outfits worn by NBA players and regularly gets DMs from players asking to be posted. The NBA has a podcast called Running the Break that is mainly dedicated to talking about NBA fashion.

I only watch football during the Super Bowl but I know who Joe Burrow is because I get 5000 edits of what he's wearing on the concrete runway every week of the NFL regular season. Same with Travis Kelce, Stefon Diggs or Odell Beckam Jr, but you never see that phenomenon extend to hockey.

Player Revenue

In 2018, LeBron James help his sponsors make $137 million dollars in revenue. To put that amount into perspective, that’s approximately 1.66 NHL teams’ total cap space. That same year, Steph Curry made his sponsors $39 million dollars. Roger Federer, one of the greatest tennis players of all time, left Nike in 2018 after spending 24 years with the brand, to pursue a more lucrative 10-year $300 million dollar partnership with Uniqlo. That Uniqlo deal alongside other business deals made Federer the first-ever billionaire in tennis.

A common complaint amongst NHL fans is that players do not get paid enough, both in terms of much work is required to be an NHL player and in comparison to what athletes of other North American sports leagues make. If you’re not going to remove the salary cap, which is not going to happen anytime soon, you should at least facilitate a way for your players to get brand deals so that they can make money outside of hockey. There are many players who have an affinity for fashion that you may not know about: Nikita Zadorov, Klim Kostin, Mathieu Joseph, Mikhail Sergachev, Liam O’Brien, Adam Lowry, Yanni Gourde, Alex Wennberg etc. I always wonder how much these people could have a greater impact on fashion and pop culture if they were not limited by the scope of the NHL dress code and could branch out to a wider audience.

Creativity

This is my shortest and most self-centred point. Every NHL team plays 82 games a year. At the time of this article being posted, the 2022-2023 NHL season has yet to reach its conclusion, but if I am to estimate how many game-day outfits I have seen so far, that number is comfortably around the 500 mark. There’s only so much you can do with a suit. Yes, you can wear it in a different colour, add sunglasses, wear it with sneakers, or choose some cool lining to flash to the camera. I can usually tell when a suit is a repeat. The dress code sucks a part of the fun of game days. At the end of the day, a suit is a suit, it’s meant to not be visually interesting to look at.

Once again, the NHL has its fair share of fashionistas and you clearly see what they can come up with during the off-season when they are not limited to a suit and tie and get to flex their creativity genius.

* Addendum #5: The Met Gala is a fundraiser, so large companies buy tables and then invite guests to their tables. Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour has the final say on who gets to go. While I do not know Anna Wintour personally, because why would I, but it is a known fact that she, like myself, is obsessed with Roger Federer. As a fellow RFed stan it is my hypothesis that if you like Roger Federer, you will like Henrik Lundqvist. They are both European gentlemen, highly respected figureheads of their respective sports. They are the same person in different fonts.

Closing Thoughts

If the suit was just that, a suit, there would be no discourse or protest when a team removes it or discusses the possibility of reforming it. This is by no means an admonishment of all dress codes or uniforms. They aren’t all inherently negative. The NHL as a league is slow to change and has a fierce embrace of tradition, so I do not anticipate an overnight change in this regard. Some changes are happening. The NHLPA has been advocating for a few years now for the relaxing of the dress code by all teams. Certain teams have allowed for a more relaxed take on their dress code that encourages some personal creativity. But beyond that, I think it's important to reevaluate the NHL’s relationship with tradition, conformity and how those views get embedded, consciously or not, into what people are and are not allowed to wear.

Works Cited

De Casanova, E. M. (2015). Buttoned Up: Clothing, Conformity, and White-Collar Masculinity. Cornell University Press.

Allain, K.A. (2015). ‘‘A Good Canadian Boy’’: Crisis Masculinity, Canadian National Identity, and Nostalgic Longings in Don Cherry’s Coach’s Corner. International Journal of Canadian Studies 52, 107-132. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/611958.

Cambers, S., & Graf, S. (2023, February 14). Letting Roger Federer leave Nike for Uniqlo was an ‘atrocity,’ says former Nike tennis director. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2023/02/14/tennis/roger-federer-nike-mike-nakajima-tennis-spt-intl/index.html

Flammia, C. (2021, February 12). How the NBA’s Best-Dressed Players Turned the Tunnel Into a Business. Esquire. https://www.esquire.com/style/mens-fashion/a27760825/basketball-fashion-style-nba-business-concrete-runway/

Barry, B., & Weiner, N. (2017). Suited for Success? Suits, Status, and Hybrid Masculinity. Men And Masculinities, 22(2), 151–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184x17696193

Rickman, J. (1931). The Psychology of Clothes. By J. C. Flügel B.A., D.Sc. (London: Institute of Psycho-Analysis and Hogarth Press. 1930. Pp. 257. Price 21s.). Philosophy, 6(22), 269-270. doi:10.1017/S0031819100045435

This is by no means an exoneration of Evander Kane or Ray Emery’s actions, as both men have committed morally and legally reprehensible actions. However, I believe it is appropriate to ask if some, and I do mean some, of their actions would warrant the same amount of backlash if they were not black men in a sport that is 97% white (i.e., Sidney Crosby would not receive the same amount of pushback as Evander Kane if he posted the money phone picture).